This was a pretty big year for me. I’d just graduated film school, but in the midst of a writers’ strike I found that I couldn’t really put everything I learned from then into good use just yet. But it didn’t stop me from watching films all throughout the year, and even in what’s admittedly a trying time for myself, I wasn’t going to let it all stop me. It also felt like the first time in quite a while where I could really go on out to push myself to become more proactive with my writing.

But a part of why I’m always at least a little bit apprehensive whenever I write my lists of the best films of the year comes down to the fact that I always feel like I haven’t quite seen enough. For some of the past few years, I’ve always saved writing these lists all the way until either late January or mid-February, particularly because of those releases that didn’t end up opening very wide until the start of the year. And sometimes I’ve felt like the push to watch a little more sometimes stalls my own productivity in a sense.

There’s also the afterthought about the publishing of the list and then having it dogged by the people who will keep asking why some of their own favourites are missing. I’d know this from experience the moment when A. O. Scott was asked about why he didn’t have Top Gun: Maverick on his own top ten list, supposedly as it was a sign of elitism or “wokeness” (I thought it was a very good movie, but nowhere near close to top ten material). But I’ve never understood any of that. All because it’s not my own top ten list, it’s someone else’s, and I don’t see any worth in getting mad someone else has a certain movie in their lists.

Because these top ten lists aren’t supposed to reaffirm what you or some other person who only saw a handful of movies in the year have thought. They’re reflective of the person who’s making the list, and they’re just supposed to open more doors for you, especially while we still have the chances to take. So without further ado, these are my favourite films of the year, from the many that I was able to catch – and I think I feel pretty rock solid about these picks for the most part.

10. Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet)

This French courtroom drama took home the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival this year. But perhaps the first thing that catches me about a movie like this is the fact that it never answers something as simple as whether or not Sandra had a role in her husband’s mysterious death. Yet by the end of the movie, that didn’t matter to me at all. Which is only a part of what it is that made Anatomy of a Fall so brilliant in my eyes; it’s a courtroom drama that takes down the inherent flaws that we see in the process, but it’s also a hugely gripping film about the way that familial relationships are destroyed by character assassinations and the need to rush to judge for a guilty or not guilty verdict.

And it’s also just so quietly devastating, regardless of how you view it for Sandra. Which I think might as well be the key to the film’s success, you’re never sure what to make of her. But that’s also how you end up feeling for the people around her, whether it be her lawyer or her blind son, which I find to be maybe the most compelling case you can make for a film like Anatomy of a Fall. The answers aren’t nearly as simple as you might want them to be, but the lack of certainty surrounding Sandra’s case, and the exhaustion you’ll feel from being within that space – only makes you feel for what’s going on around her. It’s not always black-and-white, it’s more complicated, but that’s just human nature.

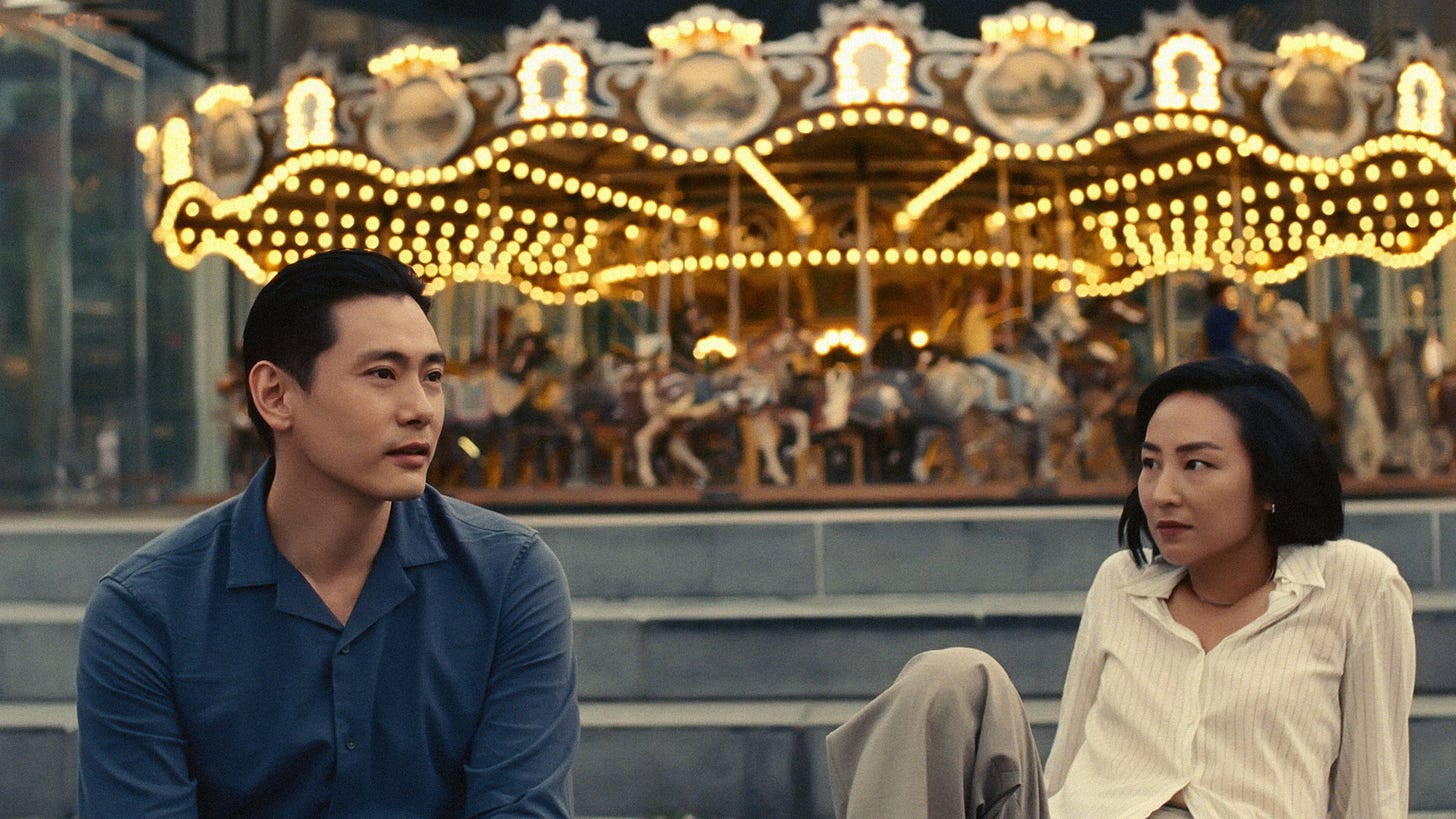

9. Past Lives (Celine Song)

Here is maybe the best debut feature film that I’ve seen within the past few years, all about a theoretical love that could have been. In telling this semi-autobiographical story to the screen, writer-director Celine Song brings forth a tale about “what if,” first about the experience of being an immigrant, where your past upbringings still play a big factor in shaping you into the person that you are in the present. But I also think that the most beautiful moments in Past Lives are spelled out from the fact that Celine Song makes a case about how she’s pondering about what the people she knew from before she moved out of South Korea are up to in the present.

While watching Past Lives, I feel that it’s not just all about a “what-if” romance. Instead, it’s all about the missed opportunities that disappeared in the blink of an eye. All those missed opportunities that could have happened if Celine Song had actually stayed in South Korea, and then maintained exactly what she loved doing most. Although it might just as well be worth asking, would Celine Song still have been able to make something as beautiful as this if she stayed behind? Available on home video and on VOD in Canada.

8. Perfect Days (Wim Wenders)

A new film directed by the great Wim Wenders in the Japanese language, Perfect Days is a film all about what seems like something that sounds so mundane. But sometimes those simple quirks we find in everyday life tell their own story. Every moment in Hirayama’s life feels like it’s on a set path. And the occasional drift comes a long way, reminding you that there’s more to life than just having a perfectly set routine to define it all for you.

From the moment Perfect Days starts, it feels like Wim Wenders is showing you the ideal way to go about your day. Cleaning public toilets for everyone else’s use, putting on some good music, and reading a good book. It’s the sort of peacefulness that I think speaks volumes even when Hirayama isn’t saying much directly. Something like Perfect Days feels like a release from the stress you face in everyday life, and I just came out of it wanting to put on a Lou Reed album, and just keep on hanging on. Opening in a limited release in Canada in February.

7. May December (Todd Haynes)

I caught this film on a beautiful 35mm print earlier this year. Perhaps it’s the only way that I could ever want to watch something like May December, the brilliant new film by Todd Haynes. When you think about the story that May December was inspired by, you can’t help but feel like there’ll already be people wanting nothing more than to sensationalize the circumstances at hand. Of course, that matter at hand is the Mary Kay Letourneau case, in which a 34-year-old woman had initiated a sexual relationship with the 12-year-old Vili Fualaau – and eventually got married to him following her release from prison.

I shouldn’t need to tell you more details about that story, because it’s a very devastating one – and a simple Google search of Fualaau’s name would often center Mary Kay Letourneau. Todd Haynes found a brilliant way of telling this story, by framing it through a story of someone who were going to play a part in a movie inspired by this scenario. And in letting it play in that manner, what Todd Haynes presents is both a very funny and damning indictment of the exploitative nature of the media industry’s desire to cash in on a story where people are still hurting. And in turn, a very quietly devastating portrait about the aftereffects of grooming, especially under the shadow of the spotlight. Available to stream on Netflix.

6. Killers of the Flower Moon (Martin Scorsese)

Few filmmakers have remained ever so consistent through their years quite like Martin Scorsese has. There’s already a lot worth talking about with regards to whether or not he’s the right person or not to tell the story he chose to in Killers of the Flower Moon. But Scorsese makes it evident that for him, it’s something he wants to reckon with. It’s worth reckoning with, because we know that stories like this would not be told for the audiences that it will reach, without at least a supposed “hero” figure coming out of it at all. Instead, what Scorsese makes of this story is less a story about finding who’s behind such an atrocity, and more about how these acts of violence are also the foundations for present-day America.

Killers of the Flower Moon is a staggering portrait of human greed, and all about how these horrific acts of violence are nothing more than mere afterthoughts for those who continue perpetuating it all through time. Perhaps the saddest thing about a film like Killers of the Flower Moon, is coming out of it all, knowing that these acts of violence against Indigenous people living in America, still exist in some form. And those few times where it’s acknowledged, still reinforce a racist narrative with the noble white man saving the day. It’s an American tragedy told the way that it should be, especially if it were to be told by someone of Scorsese’s ilk. Available to stream on Apple TV+.

5. Oppenheimer (Christopher Nolan)

During Oppenheimer’s initial run, of course, you couldn’t ignore the phenomenon that spurred from its simultaneous release with Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (also a very good film in its own right). But for me, Oppenheimer wins between the two – in part because it feels like Christopher Nolan has put everything he’s learned from having been within the blockbuster game starting with his Batman films and pushed himself for more. In making a biopic about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man whose name has been made as the father of the atomic bomb, not only has Christopher Nolan made what might be the best biopic of the past few years, but a blockbuster that will define both the decade and his career.

Oppenheimer feels like an apocalyptic movie from the first frame onward, but in how Nolan brings us as the viewers to identify with someone like J. Robert Oppenheimer, not only are we being made to understand him as a person, but his role working for a government ready to throw him out once he was inconvenient. Cillian Murphy’s first leading role in a Christopher Nolan film is not only a career-defining role, but it’s one that realizes the humanity present in a complicated figure like J. Robert Oppenheimer – and ultimately what it felt like for him to be a tool for the American government to retain their supremacy. Available to own on home video and rent on VOD.

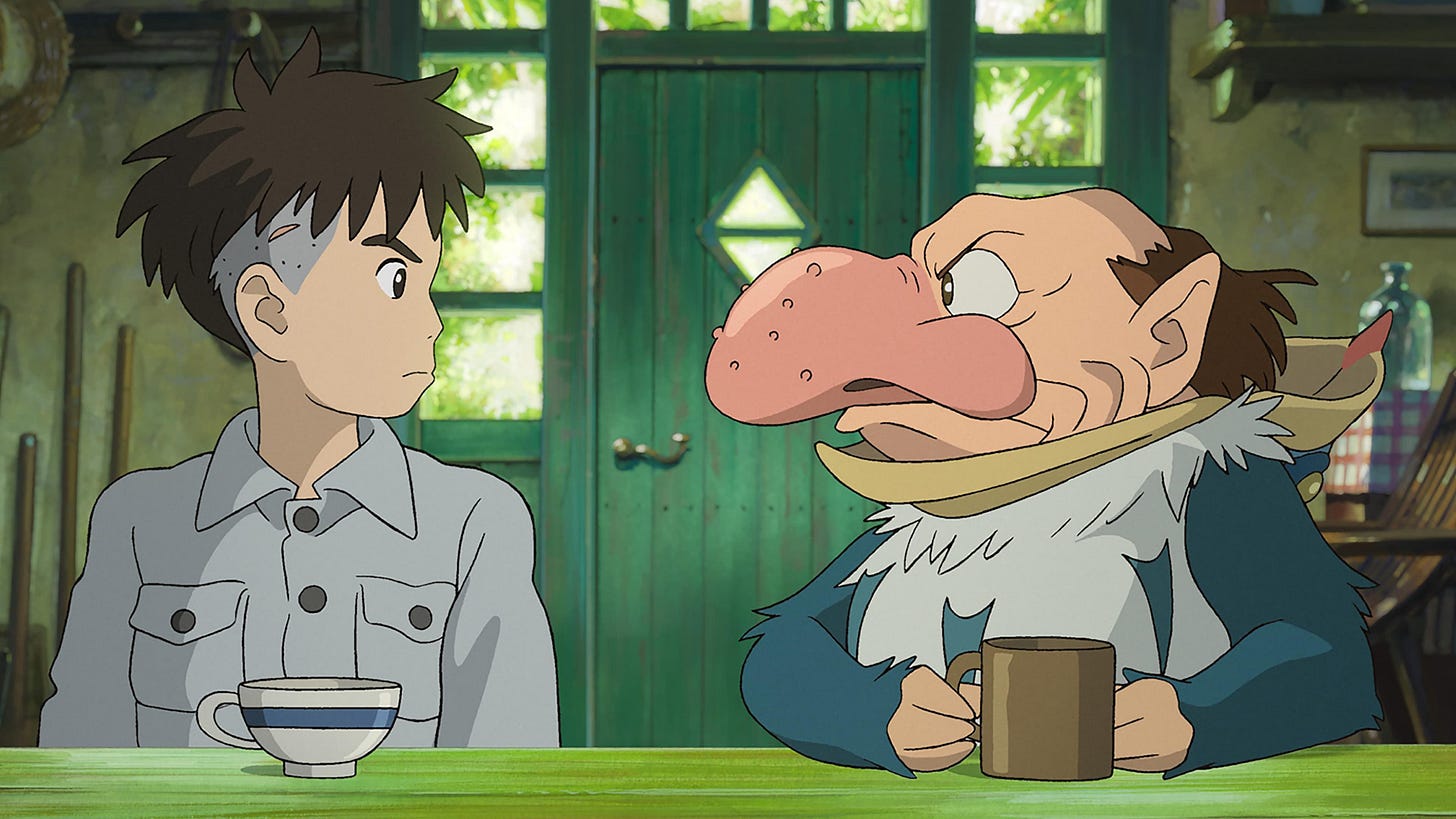

4. The Boy and the Heron (Hayao Miyazaki)

Hayao Miyazaki is no stranger to the retire-unretire game, quite like Steven Soderbergh had shown not long beforehand. The Boy and the Heron, the animation legend’s first film since The Wind Rises feels like a personal statement for the director, in that it feels like a perfect culmination of everything that his career has led him to around now. It’s a great film all about the nature of storytelling, but also how this has helped him within such an early phase of his life. Not only is this maybe the most beautifully animated film of the year, but it feels like Miyazaki working in a more contemplative phase with what limited time he has left with us.

In a career that’s been built on masterpieces one after another, The Boy and the Heron continues that streak of consistency for Miyazaki. It’s a film all about childlike wonder, but also how this has become an important tool for him to grow as a human being – and ultimately, how to live life moving forward. After all, given the film’s original Japanese title being How Do You Live?, The Boy and the Heron feels like Miyazaki reaching out to his audience, wanting nothing more from them to live their very best lives moving forth. Because you can’t let your childhood escape you so easily, instead, it’s just a springboard for life going onward. Currently in theaters in Canada.

3. Poor Things (Yorgos Lanthimos)

This bizarre Frankenstein-esque story is a brilliant mockery of supposed “polite society” by way of Greek auteur Yorgos Lanthimos and collaborator Tony McNamara (who also co-wrote The Favourite), but as some have said, it feels like a film all about someone who was formed to fit an ideal realizing freedoms within the world she inhabits. They go far and beyond, from sexual freedoms to the ideologies that govern us, but as Emma Stone shows us through Bella Baxter’s eyes, it’s all about the reclamation of the self.

Poor Things may be one of the funniest films that I’ve seen in a long time. It’s also one of the most maddening, gorgeous, and demented portrayals of the cruelty in a world defined by a superficial status quo. Poor Things feels like an act of rebellion, which might be more than enough to render it one of the year’s most unique films. Truth be told, I’ve never always been a fan of most of Yorgos Lanthimos’s films at the present, but Poor Things might be the most that I’ve clicked with his work. Currently in theaters in Canada.

2. The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer)

After Under the Skin, anticipation for what would become Jonathan Glazer’s next film could deliver. To say the least, he delivers one of the most haunting films of the year with The Zone of Interest, a movie all about evil stripped to its barest. The Zone of Interest is a film all about the Holocaust, but from the point of view of Nazi commandant Rudolf Höss. What you’re seeing in The Zone of Interest is a haunting portrait of evil, all the way down to the most mundane and unrewarding aspects of perpetuating an atrocity.

But I think what strikes me most about watching The Zone of Interest, is knowing that Jonathan Glazer’s choice to frame a story of supposedly ordinary life within this backdrop, just implies a sense of complicity at hand. We don’t even see the war crimes being committed on the screen, we just know it’s going on in the background, but even today, acts of genocide are still being committed like this. By that point, you realize that The Zone of Interest isn’t just a film all about the Holocaust, as much as it is about the way that trying to go on your ordinary lives amidst an ongoing genocide, just simply keeps the oppressors in power. It’s a very draining movie, one that’ll stick with you long after it ends. Currently in theaters in Canada.

1. Monster (Hirokazu Kore-eda)

What exactly is it that makes another human being a “monster,” so to speak? Could it be that they’re just different from people around them? Or could it be that they’re not willing to understand what’s going on? This question is what surrounds Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest, a brilliant film that shows there’s no simple answer. In Monster, we’re made to see a complicated scenario by manner of how the adults around Minato ultimately have a limited perspective about what’s going on, and can’t really be made to understand either. But each of these points of view carries a different piece in a greater puzzle, one that becomes more slowly devastating.

Perhaps adding more to what makes Monster so devastating is knowing that this is the final film to be scored by the great Ryuichi Sakamoto. And the musical cues heard in Monster only make it all the more haunting, because Kore-eda shows us that children can be our own gateway to understanding the world, if only we’re willing to listen. Even in a situation where people want nothing but the best for those we love, Monster asks us to look beyond what we normally see. For it might take an act as simple as understanding what children are going through to understand a whole other world – and Kore-eda brings out one of his most devastating films to date in a very beautiful plea. Currently in theaters in Canada.

Honorable Mentions

Godzilla Minus One (Takashi Yamazaki)

Showing Up (Kelly Reichardt)

The Beast (Bertrand Bonello)

John Wick: Chapter 4 (Chad Stahelski)

The Holdovers (Alexander Payne)

Thanks for making it to the end! If you like what you see here and you aren’t subscribed yet, please do so down below!