In Defence of Squid Game Seasons 2 and 3

The concluding seasons of Netflix's most watched show are getting a bad rap from fans of the first season, but how much of it is earned?

This piece contains occasional spoilers for Squid Game. Please read at your own risk.

When the first season of Squid Game dropped on Netflix in 2021, it ended up becoming Netflix’s most-watched show in the streamer’s history. I don’t think that it’s difficult to see why Squid Game ended up becoming as massive a hit as it did: it’s a television show whose themes about capitalism being a game where one risks life or death have a greater resonance. It also didn’t come off as any surprise to me that Squid Game became anywhere near as big a phenomenon as it did, in part because it came out at the perfect time: a whole year after the COVID-19 pandemic had left us staying inside our homes, and South Korea has experienced a cultural boom. It only became fitting that Squid Game would be a natural part of that boom, so the fact it would end up as Netflix’s most-watched series from its release was not a surprise to me.

The moment I watched the first season, I found it quite good. Personally, I didn’t quite find it to be nearly as revelatory as many did, especially as I’d been watching many South Korean movies and shows in the past. Nonetheless, I appreciated what Hwang Dong-hyuk was doing with the concept of poverty-stricken South Korean people playing children’s games as their only way of getting out of their situation. The sets are incredible: I was particularly taken aback by the show’s sixth episode, “Gganbu,” in which the contestants are made to play a game of their choice involving marbles with a partner of their choosing. It’s a very heartbreaking episode, and I feel that even when I didn’t always love the show, it was this moment that really ended up getting to me more than any other. It wasn’t exactly the moment that made me understand its resonance, because I saw that from the first two episodes onward. But it was a moment where I realized what it was capable of.

And it was not exactly a show that’s free of problems. For one, I found the subplot involving Wi Ha-jun’s detective Hwang Jun-ho pointless in the first season. Him being the younger brother of the Front Man didn’t really add very much, especially in relation to the relentless violence we’re seeing within the games themselves. The one thing I had hoped for, especially in later seasons, was that this angle would be explored more. And it clearly creates a more complicated dynamic, given how Jun-ho conceals information on whom his older brother actually is at the start of the second season. I thought that this would be an interesting direction to take the series, given the fact that the Front Man enters the game as a player in Season 2, taking number 001 – much like Oh Il-nam had done.

I was hoping that a second season would erase many of these gripes, but I can’t say that all of them were cleared. That’s not the point of this piece though, rather instead I wanted to address the most common criticisms that fans had for these last two seasons. Some of these were genuine: one of them being the final two seasons not feeling like individual seasons, but a single season split in half. Even though the first season of the show had ended on a cliffhanger, I think that it signalled one story had come to an end and another was about to begin. Season 2’s cliffhanger felt like a single story being half-fulfilled, and then Season 3 came along to feel like the second half. Given the fact that these two seasons were shot back-to-back with each other, it’s not hard to feel as if they could easily have created one full season instead.

Meanwhile, another common criticism comes from the casting of Park Sung-hoon, a cisgender male actor, as the transgender player Cho Hyun-ju. I also find myself sympathizing with anyone who takes issue with this: because the casting of a cis performer as a trans character plays into a form of erasure. It feeds into a perception that people would have of trans people, in that they are men dressing up as women or women dressing up as men and vice versa. While I appreciated Park Sung-hoon’s performance and the fact he did not let his portrayal of Cho Hyun-ju devolve into reinforcing such stereotypes, there was a missed opportunity nonetheless. Hwang Dong-hyuk seems to agree, as he had hoped to cast a transgender performer in the role, but LGBTQ+ people are still marginalized in South Korea, so this casting could not be fulfilled properly. Park Sung-hoon did the best he could, and it is a very good performance he brings forth, so I don’t want to write this with any ill will directed at him.

Yet, given the amount of stress that creator Hwang Dong-hyuk had underwent in the making of the show’s first season, you can tell that the creation of another would be exhausting. This only might have been inevitable with the fact that Squid Game quickly became Netflix’s most-watched series, so the franchising of it was not out of the question. This was maybe the worst thing that could happen to the show, considering the fact that Hwang Dong-hyuk had originally written the drafts based on his own experiences with poverty. The fact that it had taken him over ten years before someone had given him the green light is not quite the uplifting story of creative victory one would think it is. Instead, it’s only reinforcing the point that he wanted to make from the very beginning. The property might have raked in over $900 million in profit for Netflix, but Hwang Dong-hyuk didn’t see nearly as much of a bonus from the show’s surge in popularity.

And despite all of these gripes, I might as well drop a hot take: in my eyes, Season 2, is where this show has peaked. Yes, I agree that its finale feels a bit underwhelming. I’m also disappointed that the subplot surrounding detective Hwang Jun-ho didn’t really amount to much. And yet, I find it to be the series’ best season because I think that its willingness to explore the roots of poverty in present-day South Korea is very admirable. The contestants are all trying to get themselves out of dire circumstances by fighting for their lives, but it’s also where Squid Game’s main thematic drive, feels most potent. This was still felt through most of Season 1, but Season 2 having a wider array of contestants from the many walks of life may have created a greater resonance.

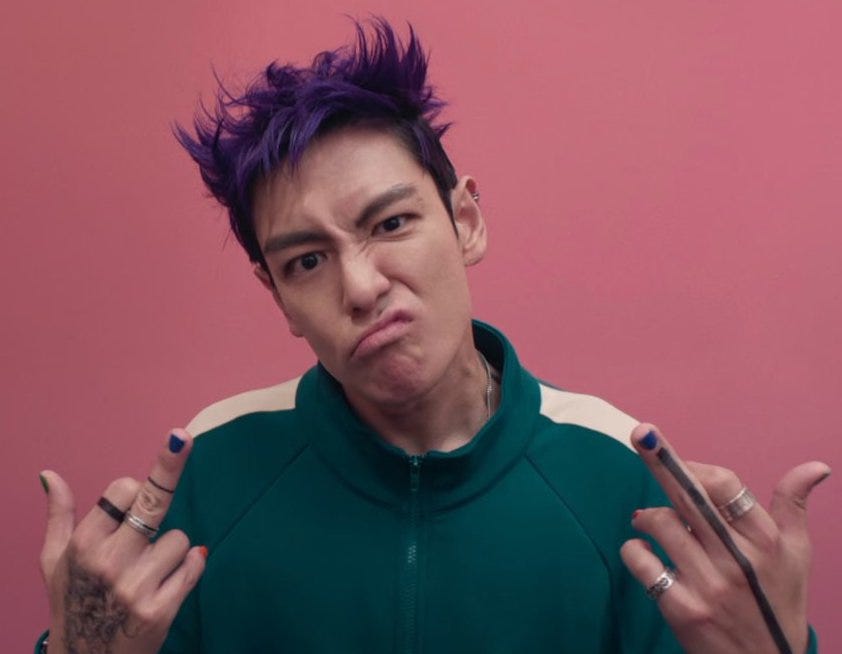

To start, I’ll talk about one of the series’ most divisive characters, Thanos. The casting of T.O.P, formerly a member of the K-Pop boy band BigBang, was controversial in South Korea. This stemmed from a controversy surrounding his conviction owing to marijuana usage in 2017. Compared to a villainous presence like Jang Deok-su in Season 1, the goofy antics of Thanos may not have played all that well for Korean viewers. Despite this, I actually loved Thanos. Another gripe I’ve had with Squid Game stems from the series having an overtly self-serious tone regarding how it approaches its own lore. When you think about how many Americans are into K-Pop despite having no connection at all to the cultural roots, Thanos feels like the inverse: he’s a rapper who’s into American movies in that same manner. It all comes clear from the stage name, being taken from the Marvel villain of the same name, but a good chunk of his lines being in English just feel funny to listen to. I found his presence was a welcome one, as the comic relief he provided only helps capture the darkness of this premise.

I also may go ahead and say that while I’m still not too fond of the Hwang Jun-ho subplot, I was, however, fond of another subplot involving another North Korean defector. The most well-loved character, aside from Lee Jung-jae’s Seong Gi-hun was HoYeon Jung’s Kang Sae-byeok, who was a North Korean defector. For series creator Hwang Dong-hyuk, it’s clear that this issue is one that means a great deal to him, given how North Korean defectors are a vulnerable minority group within South Korea. Considering the fact that we never really saw much of the masked soldiers within the show’s first season, Kang No-eul’s presence felt like a needed addition. It was needed in the sense that we only saw a glimpse of it when one of the workers is unmasked, but also because of how we saw that these workers were human beings trying to make it through.

And I might even say, Kang No-eul actually had one of my favourite storylines within the show. I thought that giving the soldiers who work behind the scenes at the games a sense of humanity was a smart decision, because we’re seeing a different side of how poverty affects those related to the games. While obviously, the players are in it for a gigantic cash prize, the masked soldiers are working there like it’s a day job. Some clearly take pleasure in killing the losers, but perhaps there are workers like Kang No-eul who don’t enjoy what they do. The opportunity for her to redeem herself is made more evident in Season 3, as she’s opting to fight not only a group of organ harvesters who mutilate players after they are eliminated from the game. And it all comes forth in her own relationship with a player who wants to help his daughter, who’s suffering from cancer. While I share the disappointment that it feels a bit far-removed from the story of Seong Gi-hun, I think a human perspective on the soldiers’ side helps us understand this world better than seeing them as faceless entities.

Perhaps the most controversial element of Season 3, though, is the VIPs and the performances of the actors. I’d talked with friends on social media who lamented the fact that they felt inhuman, and the performances rang as awkward presences tonally. Maybe it’s true, but I thought this was entirely deliberate, and it gave them a very eerie vibe as they take pleasure in watching poor people constantly fight one another because they view themselves better. I think after seeing so much of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos in the news, the fact that the actors playing the VIPs as shallow, annoying archetypes felt very fitting. It’s fitting because it feels like this was Hwang Dong-hyuk’s acknowledgement of Squid Game’s viral popularity on YouTube, with creators like MrBeast and the Stokes Twins recreating sets and missing the point of the show entirely. Granted, this becomes another issue entirely – but given the very subset of the human population they represent, I can’t say that I found it very out of line. I thought that their stilted deliveries worked to create this dissonance between the upper and lower classes, and I can’t imagine any other way to go about presenting them after what we saw in Season 1.

Last but not least, with rumours about an American counterpart being produced by Netflix with David Fincher’s guidance, the final scene could read like a means of tying in. This was shot down by Hwang Dong-hyuk himself, who said that the very sudden celebrity cameo of Cate Blanchett, was chosen because he wanted someone who would make an impact with one or two words. It feels perfectly in line with Gong Yoo playing the recruiter in the first two seasons, considering Gong Yoo’s own popularity in South Korea as a likeable screen presence playing against type. But the casting of Cate Blanchett as the American equivalent feels like it builds off that essence: a recognizably comforting face would lead you down a darker path. With how the first season establishes Seong Gi-hun’s daughter having relocated to Los Angeles, I can’t imagine any other way to end the show. I don’t think it’s Hwang Dong-hyuk’s fault that Netflix would muddy this by making an American counterpart, but intentions feel misread if it turns out he had no part in the American show too.

There are genuine criticisms that people have shared about Squid Game’s final two seasons that I do agree with. But I can’t say that I agree with most of what you’ll find on social media. Most of it feels like misreading of Hwang Dong-hyuk’s intentions, considering a tendency to assume the worst. I don’t even love the show nearly as much as most seem to, but I’m glad for its popularity. I hope that Hwang Dong-hyuk goes on to make great films or television shows with Squid Game finally being over. The pressure clearly was on him after he ended up making what became Netflix’s most-watched show, so I can’t blame him for being exhausted. Perhaps that might be why I’ve become so charitable for these last two seasons, even while I agree that the last season was the weakest overall. Though after seeing so many comments from disappointed fans from these two seasons, I couldn’t help but feel like it all rang as being too ungenerous. I certainly didn’t plan to write over 2000 words on a show I didn’t love as much as the rest of the world did when it first dropped, but here we are.

Thanks for your insightful essay! Ideas are spot on, especially that one about the vips, their vibe was definitely off but it seemed like a deliberate way to show how shallow and inhuman they are.

Personally, I’ve genuinely enjoyed every season of Squid Game. Hwang Dong-hyuk consistently delivers storytelling that’s bold, layered, and unforgettable. That said, I can’t help but feel nervous about what an American version might look like. My biggest fear is that it could lose the raw authenticity that made the original so powerful.

Still, I understand why Netflix wants to continue the series and honestly, there’s huge potential in exploring an American setting. The U.S. is already living out its own version of the game in many ways: debt, desperation, performative politics, and profit over people. If done right, Squid Game: America could be more than just a spin-off it could be a brutal, necessary reflection of our reality.

https://open.substack.com/pub/underdoglens/p/squid-game-season-4-belongs-in-america?r=350k6l&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true